Social Media and the Conceptual Distancing of Knowledge and Expertise

Sunday, October 21st, 2012In his highly readable book What is Education?, Philip W. Jackson, Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus at the University of Chicago, attempts a total rethink of education ‘from the ground up.’ Taking a John Dewey lecture from 1938 as his lead, he proceeds to drill down into what is the ‘essence’ of education. Jackson builds his arguments around a series of largely corresponding dialectical relationships, primarily drawn from Kant and Hegel, from Dewey himself, and from the theologian Paul Tillich.

In the concluding chapter, Jackson draws on a previous text of his (1986) to introduce two corresponding pedagogical traditions, the ‘mimetic’ and the ‘(trans)formative.’ There is, he suggests, an instinctive resemblance between these and the ‘informing’ and ‘forming’ goals of teaching; that is between the transmission of factual and procedural knowledge, and the shaping of character. But Jackson’s most recent thinking on this has caused him to re-evaluate his position:

“I now see it as involving not only those teachers we encounter face-to-face but also those whose influence has been far more distant and symbolically transmitted.” (88)

He speaks warmly of the ‘enduring impact’ of key philosophers and thinkers on his own learning, gained primarily through the reading of original texts. And whilst acknowledging the significant contribution of some of his teachers, he suggests others only played a peripheral role:

“Many of those teachers I have long forgotten. Their influence was transitory, even though it may have left me more knowledgeable and better able to do this or that. They’re like the textbooks that, once read, were set aside and never consulted again. They may have served a very useful purpose at the time, but the mark they left turned out not to be personally indelible.” (89)

Jackson here is blurring the distinction between primary and secondary, and physical and symbolic sources of knowledge, whether they are realised through the student’s direct relationship with a supportive teacher, or through the inspirational words of a dead philosopher. This challenges the notion of ‘informing’ texts (or, if you prefer, learning content) as neutral artefacts that are utilised by teachers who exclusively provide the transformative process of shaping student understanding. Indeed, when considering the potential cultural baggage that comes with the mimetic tradition, Jackson’s initial attempt at a definition of education as “a socially facilitated process of cultural transmission” (10) is useful.

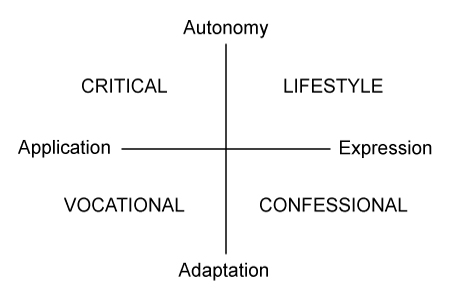

This raises some interesting questions regarding the social web. How might that social facilitation be disrupted by a student’s increased appropriation of distributed and multimodal forms of content, by her access to a wider range of sources of expertise, and by her engagement in more participative forms of content production? And what if any, do increasingly self-directed and participatory forms of enquiry contribute to the apparent blurring between the mimetic and transformative traditions Jackson describes?

What struck me most about the author’s re-evaluation was how it introduces a ‘conceptual distance’ between the source of knowledge and the student, underpinned by a ‘mutual recognition’ that Jackson – referencing Hegel – suggests is essential in influencing and shaping the student’s empathic relationship with the knowledge provider. This may be evident (or evidently absent) in the traditional student-teacher relationship. Yet the gulf between the student and expert is typically too vast to engender any sort of reciprocal relationship. As Jackson observes:

“Most of us can never be recognized by the most renowned of our intellectual and spiritual progenitors. We can only admire them from afar by reading their works or reveling in the enjoyment of their artistic creations.” (90)

One can assume this is diminished as students progress into postgraduate study and enter academia themselves. So how might the increased complexity, informality and connectivity we associate with the social web influence this act of conceptual distancing? I’ve discussed previously the potential role of social media in signposting the complex social and cultural interrelations underlying contemporary academic discourse. Further, how might the student develop and refine her conceptual distancing as she progresses into postgraduate and doctoral study, and engages in the reciprocal processes of identity transformation and recognition in her chosen field?

References

Jackson, P. W. (1986). The practice of teaching. New York: Teachers College Press.

Jackson, P. W. (2011). What is education? Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.