My thesis is examining how PhD students’ academic practices are facilitated by the adoption and use of social media. In attempting to develop a conceptual model of doctoral practices, it has been useful to look at similar examples in the literature.

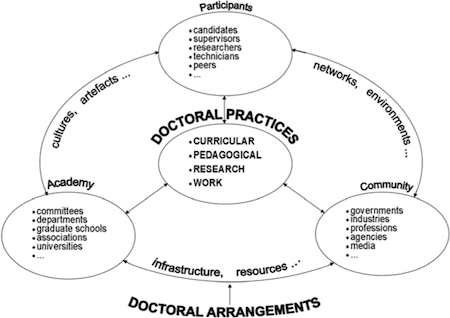

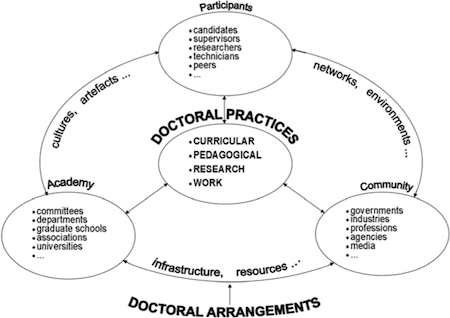

From the outset, I have adopted a holistic perspective of what constitutes doctoral study, looking beyond those activities that only support thesis-development. I’ve therefore been particularly impressed with some of Jim Cumming’s writing. His integrative model (2010) incorporates four mutually inclusive doctoral practices that describe curricular, pedagogical, research and work-based activities. These are, he suggests, in a constant state of flux, and embedded within a diverse range of relations, networks and cultures that orient around several key doctoral ‘arrangements,’ which he defines as participants, the academy, and the community.

Integrative model of doctoral enterprise (Cumming, 2010; 31)

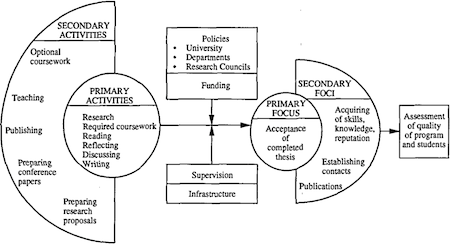

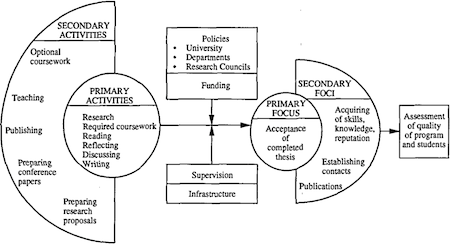

Cumming (2010) also highlights a number of previous conceptual models. Though slightly dated, Holdaway’s (1996) framework of activities and foci is the most comprehensive.

A conceptual framework of activities and foci of graduate education (Holdaway, 1996; 52)

His distinction between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ foci relates closely with a coding model proposed by McAlpine et al. (2009), in which activities are designated ‘doctoral-specific’ or ‘academic-general.’ These are mapped across 3 levels (formal, semi-formal and informal) to form a matrix of six activity clusters. This categorisation of formality seem somewhat arbitrary to me. And what do we mean by formal anyway? Is it an indicator of importance, or is it something that is scheduled, rather than spontaneous? Does formality distinguish whether an activity is optional or mandatory, or whether it has some assessment criteria? I’ve discussed the problem of ‘formality’ in doctoral education in a previous post. Even if some agreed definition is established, I think the formality of individual activities should be thought of as being highly contested (by the PhD student, supervisor(s), Faculty etc.), and as such, constitute potential sources of tension.

The conceptual model I am developing from my empirical work is no more than a useful heuristic with which to guide my analysis, which – as I’m using an activity theory-based approach – is essentially to inform the various components of the activity systems I am developing.

As such, general academic activities are of limited use. But dig deeper, and they each encompass a wide range of academic and social processes. Take conferences, for example, and you’re looking at information sourcing (call for papers), writing (proposals, abstracts, papers), disseminating (presenting), making contacts (networking), giving and receiving critical feedback, gaining recognition in the research field etc. Each of these processes (along with many others) permeates the various interrelated activities that each of my participants are engaged in. Throw social media (the focus of my research) into the mix, and you can start to build a picture of where and how they are influential, disruptive and transformative.

Multiple occurrences of these activities coalesce into a highly complex analytical framework (for each participant), but this ensures that a qualitative analysis of each of their social media experiences is highly situated and contextualised within the various practices and stages of their doctoral studies.

References

Cumming, J. (2010). Doctoral enterprise: A holistic conception of evolving practices and arrangements. Studies in Higher Education, 35(1), 25-39.

Holdaway, E. A. (1996). Current issues in graduate education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 18(1), 59–74.

McAlpine, L., Jazvac-Martek, M., & Hopwood, N. (2009). Doctoral student experience: Activities and difficulties influencing identity development. International Journal for Researcher Development, 1(1). 97-109.