I first came across Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow Theory (1990, 1996) whilst doing my MA in Falmouth, as it tied in with my research into the systems thinking and ecoliteracy of Fritjof Capra whilst doing a design project with Creative Partnerships. I’ve not looked at it since, but as I recall, flow is described as an optimal state of activity or engagement, which has become closely associated with happiness and creativity.

I’m not sure how Csikszentmihalyi’s ideas are currently perceived in the academic field, and I appreciate his concept of flow is far more complex than that which I’m presenting here. But for me, it is a surprisingly effective barometer for how I instinctively feel I am coping with studies or workloads, and more specifically, as an indicator of opportunities for creativity. By creativity, I look beyond traditional artistic and elitist conceptions. In my current role, for example, there are many possibilities for creative outlets; in exploring research methods, in formulating theoretical frameworks, in academic writing, and in disseminating and presenting research.

Arguably, such creative approaches are integral to good scholarly practice, yet I would question whether, during the course of my PhD, I’ve sufficiently developed the skills, and gained the experience and enculturation in the field to levels that satisfy any real creative attainment. It was the same to an extent with my Masters degree (in Interactive Art and Design), and with my first degree. This may be because they have commonly been undertaken following significant career or disciplinary shifts. On my MA for example, I recall spending endless hours learning new graphics software skills, which other, more experienced students were able to use exploring ideas and concepts, or engaged in the production of creative outputs.

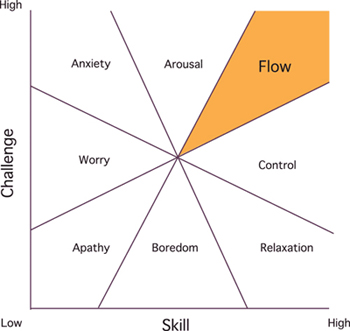

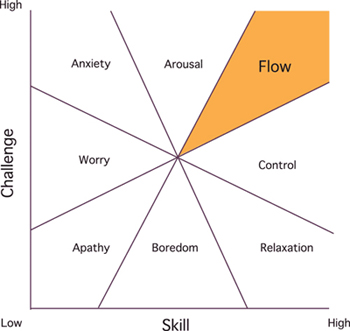

Indeed, for most of my educational career, I would roughly locate myself (above) as predominantly fluctuating between the areas marked Anxiety and Arousal. In contrast, I’d place many of my past work experiences (which have consisted of a lot of manual work) in the areas approaching Boredom.

But I do have a real sense of experiencing the flow state, often fleetingly, and occasionally for sustained periods. Its sense of immersion is tangible, yet it’s difficult to describe (it’s been compared to improvised jazz). Though, as Csikszentmihalyi demonstrates in his repeated references to blue-collar workers, flow is not the exclusive pursuit of an intellectual or artistic elite. I can certainly recall some sense of flow stacking shelves on the night shift for Tesco, after months of mastering the essential skills of product memorisation, speed and spatial awareness.

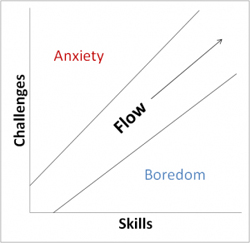

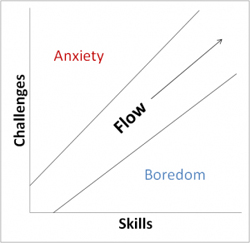

Achieving sustained flow seems then, in its simplest form, a constant and precarious balancing act between the predominant states of anxiety – where the difficulty is too high for a person’s skill level – and boredom – where the difficulty is too low. Flow is dynamic, and it seems we can fall either side very easily. I would, for example, put my experiences working as a care worker with adults with learning disabilities as wildly fluctuating between both sides.

Perhaps the parameters that determine how people identify experiences of flow differ from person to person. Those for example, with positive outlooks, or limited ambitions, may perceive far wider flow ‘corridors’ than others who are less easily contented or of a restless nature. Perhaps the corridor widens as we get older, and come to accept the limits of our aspirations.

Over the years, I have worked and studied alongside colleagues and peers who have seemed to be fortunate in demonstrating considerable and sustained flow characteristics (apparent in their general disposition, activities and quality of work). I might be wrong but this seems very much to occur with people who already have substantial foundational knowledge and experience in their chosen field, the self-assuredness and confidence to explore new ideas and take risks, and above all, the agency and motivation to be creative.

References

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper Perennial.